癸卯年夏季學術活動總結 2024 summer academic trips

過去一年,為了弘立書院成立中華研究中心,時間都花在行政方面。實際上,學術活動才是學者真正工作的核心。但學者究竟在幹什麼?讀書、寫論文、教學?如果我們說研究,學者究竟在研究什麼?對於學術界以外的人來說,學者的生活既神秘,也讓人費解。香港社會,商業掛帥,大家普遍認為對學術抱有很多誤解,認為學術研究必然是枯燥無味、莫名其妙,甚至是無用的。無用之用,本來是我們中國人原有的觀點和智慧,但西方的學者也有這種見解,像美國學者Abraham Flexner這部有趣的著作:The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge,值得一讀;還有一種見解,認為所謂無用的學問,其實一種知識的轉型,舊學問被淘汰,新學問才能出現。無論如何,讓我為大家介紹一下我個人的研究,同時揭開學術研究的神祕面紗!

由於疫情影響,各種學術會議與合作計劃一併受到延誤,如今學術活動如同雨後春筍般復甦,開展得如火如荼。學者們三年不見,現在也都紛紛聚首,爭相交流,忙於會晤。而我也一樣,暑期的幾個月,我展轉於英國、德國、中國的不同大學開授課程、拜訪學者,並參與了多場學術會議。

中文版按此。

In the past year, my time was spent mostly in administration, establishing the Chinese Research Center at the ISF Academy here in Hong Kong. However, for scholars, the core activities should be academic in nature. But what do scholars do? Often, as my non-academic friends or even family members would wonder, do scholars just read and write some books as they like, and perhaps teach some classes occasionally? Indeed, the definition of scholarship varies across cultures. Having studied and worked in universities in North America, Europe, China, Japan, India, and Southeast Asia, I have become keenly aware of the differences of perception and the actual works that scholars do or are expected to do! If there is one thing that connect them is the kind of research they do, i.e., the kind of research they are involved in that connect them both to their colleagues, and their fields at large. A genuine scholar should be a researcher who is in the forefront of their fields. They are naturally innovators and creators, not because they want to create new scholarship for the sake of it, but because by having mastered one’s own field of research and having become a authority recognised by their peers, one engages constantly with topics at the frontier of knowledge. At the frontier of knowledge, one sees many new and surprising things that others do not. This is the reason why for most people outside the academia, the interests of a scholar are often mysterious and obscure. In a very pragmatic society like here in Hong Kong, scholars are often accused of being unpractical and overpaid. Leaving aside the overpaid part, the works of true scholars are often unpractical because they are visionary, and the before their ideas are turned into something transformative and useful, they need to be properly investigated and explored. This is true for both science and humanities, as great inventions and ideas all start off from creative thinking, connecting ideas and things that may appear to be useless. On this topic, a provocative, little book titled The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge by Abraham Flexner published by Princeton University Press is highly recommended. Here, please let me share with you at least the kinds of scholarly activities I was involved in over the summer months.

For scholars and researchers, myself included, the past few months were particularly hectic since many academic meetings and conferences have been postponed during the pandemic. For the first time in years, scholars are able to see each other in person once again. My summer months were spent giving lectures in universities, visiting fellow academics, and attending conferences in multiple cities in the UK, Germany and China. Many of these activities are connected with my own field of research in premodern history of science in Asia, while some are connected with my broader interests in Buddhism, history of Sino-Indian relation, and Chinese studies in general.

1. Cambridge, UK. 19 June – 7 July, 2023. University of Cambridge / NRI Workshop: “Exploring the Senses in Chinese History: Body, Space, Spirit.”

2. Hefei, China. 9 – 26 July, 2023. University of Science and Technology of China. Two post-graduate summer courses: 1. Introduction to the history of science and technology in ancient China; 2. Reading Ancient Indian Scientific Literature.

3. Baofeng Monastery, Jiangxi, China. 27 — 31 July, 2023. Sanskrit Recitation and translation of Mahāyāna Buddhist text.

4. Qufu, China. 31 July — 4 August, 2023. Visit of traditional Chinese academies.

5. Hong Kong, China. University of Hong Kong. “Buddhism, Science and Technology: Challenges to Religions from a Digitalized World” at the Inaugural Forum “Beyond Civilizational Clash: The Coalescence of Human Civilizations”

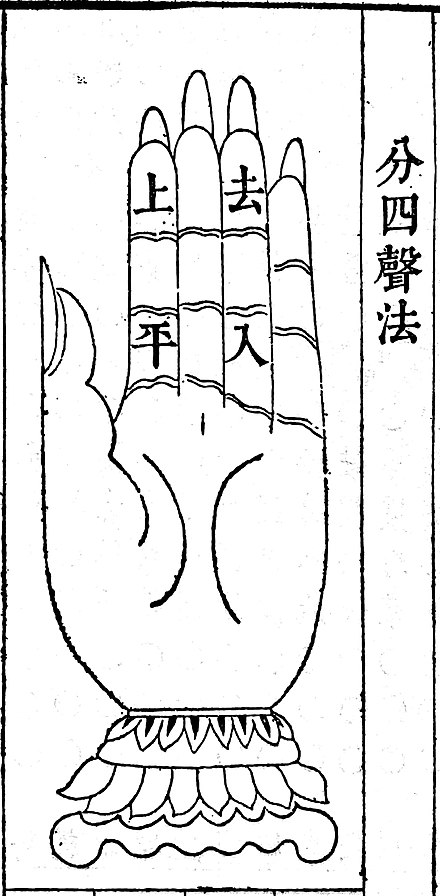

6. Hong Kong, China. 13 August, 2023. Public lecture: “Siddham and Siddham Studies”.

7. Frankfurt, Germany. 21–23 August, 2023. 16th International Conference on the History of Science in East Asia (ICHSEA). Panel: “Translating East Asian Sources: Historical Studies and Research Practice”. Paper presentation: “Sino-Indian astronomical texts in translation – Authorial intention vs. readers’ interpretation”.

8. Lanzhou & Dunhuang, China. 23—30 August, 2023. ANSO Silk Road Forum + 2nd ATES Open Science Conference. Alliance of International Science Organisations (ANSO) , Association for Trans-Eurasia Exchange and Silk Road Civilization Development (ATES). Paper presented: “Sino-Indian Astronomical Knowledge Transmitted on the Silk Road — From Kumārajīva to Amoghavajra”