In the past decade, there has been a revived interest among Chinese scholars in the history of radicalism in modern China. Among the radical Chinese intellectuals at the beginning of the 20th century were those who advocated anarchism and communism, eradicated the Chinese language and writing system, and made Esperanto the national language. Many thought that these were all crazy ideas but many serious scholars were beginning to see that all these things could well take place and they began to defend the traditional Chinese culture and language. The consequence of this intellectual battle is immense as it was the beginning of communism in China.

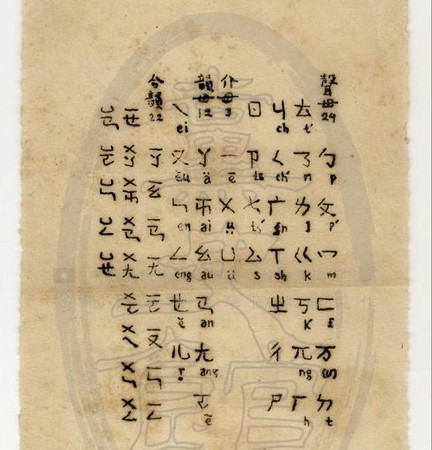

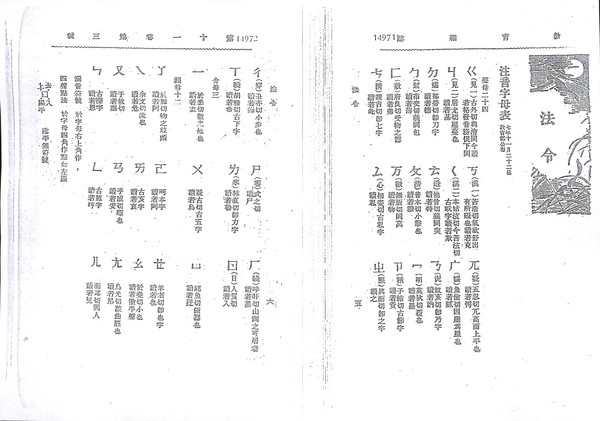

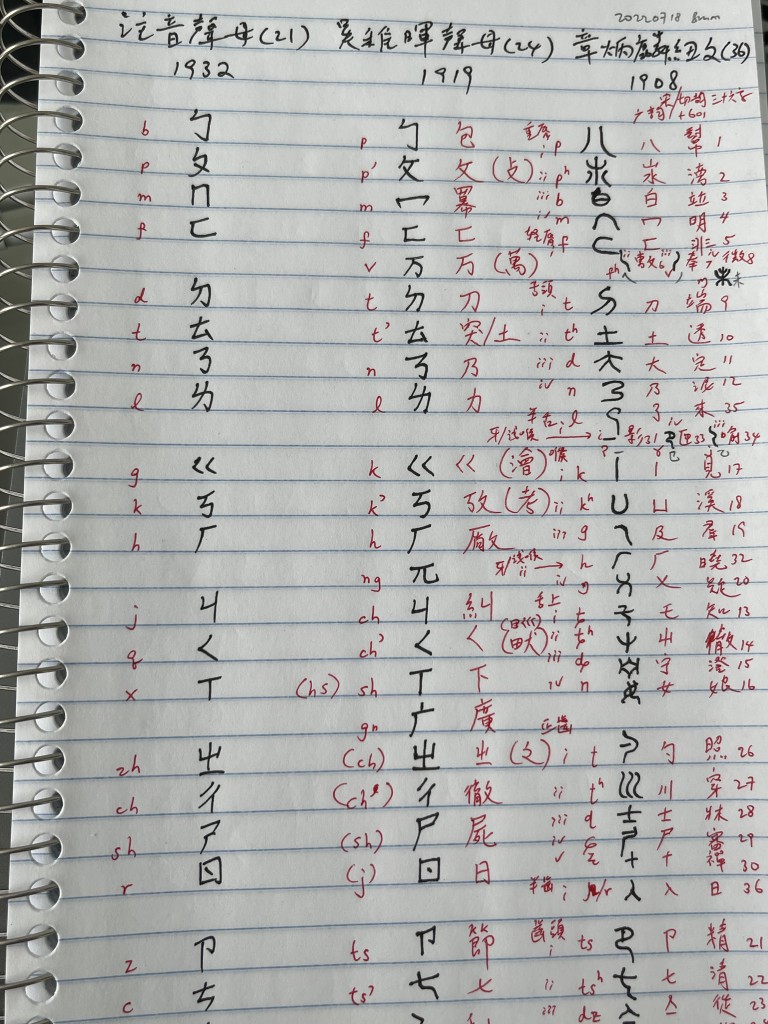

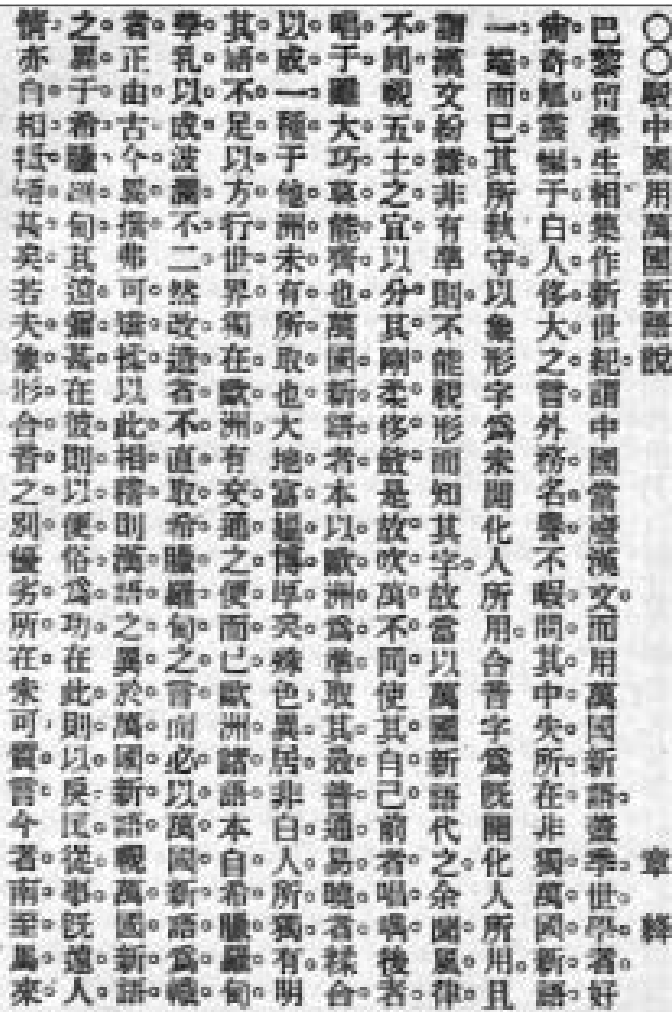

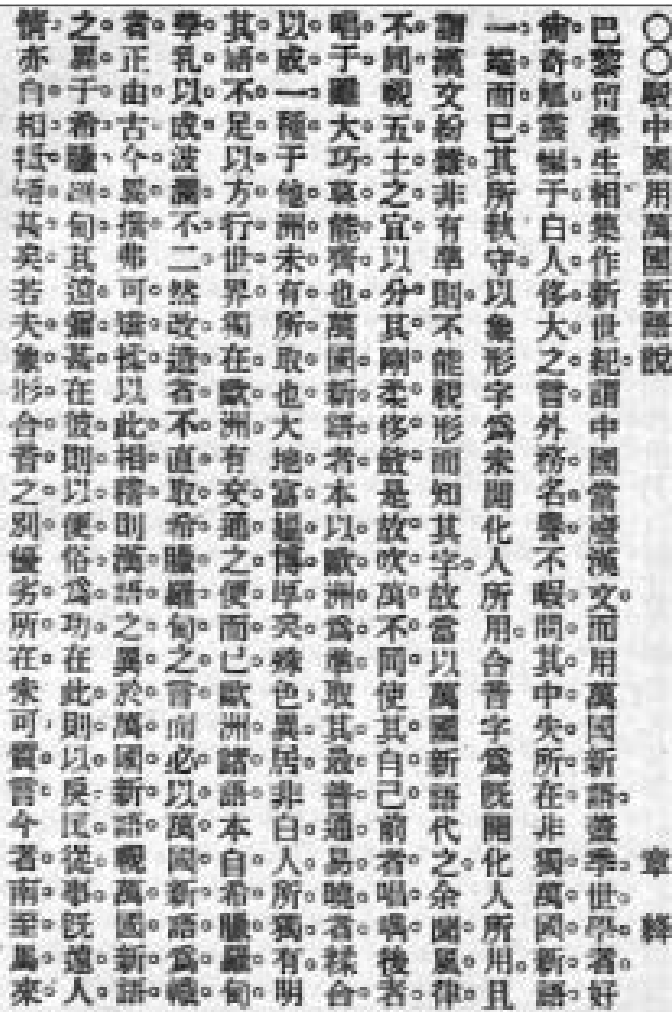

The anarchists did not succeed in eradicating the Chinese language or its writing system, but they did convince a large number of Chinese intellectuals to learn Esperanto and many scholars to engage in language and writing reform. The important scholar Zhang Taiyan 章太炎 wrote an impassioned essay in classical Chinese titled 駁中國用萬國新語說 to defend the Chinese writing system and denounced Esperanto as a futile endeavour. Zhang’s essay did not deter the Esperantists but it led to the birth of the “bopomofo” transliteration system as a solution to make Chinese “pronounceable”. The hybrid abugida system was inspired by traditional fanqie, Japanese syllabary, and ultimately Sanskrit phonetics. The “bopomofo” system continued in Taiwan, whereas in the mainland this led to pinyin using a purely alphabetic, romanised system. Another consequence of the language reform movement is the continual effort to simplify the Chinese characters — to the dismay of many, but never to replace it with pinyin as the anarchists hoped for.

My friends and colleagues are often surprised when I tell them that PRC China remains the only country in the world that officially supports the international language Esperanto and has regular radio broadcast and publication since the country was founded.

Among the more recent works on Esperanto, Chinese radicalism, and language reform, the most notable ones are those of CP Chou, Professor Emeritus of Chinese at Princeton University. While Chou’s work is informative, it is regrettably full of factual errors, and surprisingly sloppily written. Chou considers Esperanto to be futile and ridiculous, and concludes in his Chinese article that Esperanto did not help China, but rather, China helped Esperanto (!). The English version in the Brill volume is more detailed and eloquent, but a few unsubstantiated and mistaken claims remain, such as claiming that Esperanto in China was “promoted by a small group of idealistic intellectuals,” oblivious to the fact that for example in the 1980s up to a million ordinary learned Esperanto with the hope to find penpals and read foreign materials when China was still rather isolated in the world. Chou did not seem to hide the fact that he had only distaste for the language. He didn’t bother to learn Esperanto to examine the abundant sources in this simple, “utilitarian” language.

More enlightened is the work of Zhao Liming, a professor at the Chong Qing Normal University. Zhao analyses the phenomenon by seeing beyond the superficial antagonism of the ultraradicals and the conservatives. Instead he observes the tensions between internationalism vs. ethnocentrism and their effects on society and education. How the debated played out was rather interesting, as the former moved toward empiricism and science, whereas the latter moved toward humanism. Within such paradigm, the radicals, the Esperantists, the communists, and language reformers all saw themselves as progressive activists who could rescue China from its impending destruction. For them, the conservatives were impeding the progress of the new nation under threat of imperialism and colonialism. The Chinese could not bear to see their country to turn into another India and turning to radical measures were seen to be their last chance.

Selected recent works by Chinese scholars:

Chou, Chih-p’ing. ‘Utopian Language: From Esperanto to the Abolishment of Chinese Characters’. In Remembering May Fourth, 247–64. Brill, 2020.

周質平. ‘晚清改革中的語言烏托邦:從提倡世界語到廢滅漢字’. 二十一世紀, no. 137 (2013).

彭春凌. ‘以“一返方言”抵抗“汉字统一”与“万国新语”——章太炎关于语言文字问题的论争(1906—1911)’. 近代史研究, no. 02 (2008): 65-82+3.

黄晓蕾. ‘1907、1908年间的“万国新语论争”’. 中国社会科学院研究生院学报, no. 05 (2015): 101–5.

李思銘. ‘未完成的媒介革命:民国时期的汉字拉丁化运动’, 2019.

罗志田. ‘清季围绕万国新语的思想论争’. 近代史研究, no. 04 (2001): 86-144+1.

赵黎明. ‘现代中国语言变革的文化逻辑之争——重审吴稚晖与章太炎“万国新语”论战’. 江汉论坛, no. 08 (2020): 97–103.

雷鸥. ‘吴稚晖与现代语文运动的关系研究’. 硕士論文, 重庆师范大学, 2017.

高玉. ‘清末汉字汉语变革方案及其对国语建设的影响’. 学术月刊 47, no. 07 (2015): 116–24.