Unusual Greco-Indian omens of death in Mīnarāja’s Vṛddhayavanajātaka

The Sanskrit is rather corrupt and Pingree was truly not at his best when it comes to the editing of this text. At any rate, I managed to trace some interesting parallels for the various “ariṣṭa” omens in the medical section of the sixteenth century encyclopedia Ṭoḍarānanda. I can’t quite seem to find any parallels in the more mainstream Āyurvedic texts such as the Caraka or the Suśruta. It is quite remarkable that Mīnarāja attributed the materials to the Greeks. It would be very interesting if the Hellenistic sources could be identified. The next section deals with dream omens and the materials seem to bear certain resemblance to those found in the Atharvavedapariśiṣṭa, which Prof. Yano translated but remains unpublished. Prof. Yano and I plan to read through to the end of the Vṛddhayavanajātaka, before I start editing the Gargasaṃhitā sometime before the end of 2017.

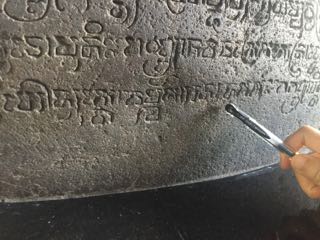

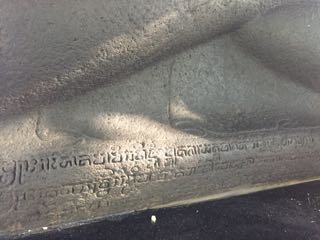

Vṛddhayavanajātaka (Pingree ed. 1976)

Chapter 64 (mṛtyujñāna)

64.01ab etad yad uktaṃ grahajaṃ samastaṃ śubhāśubhaṃ tat sudhiyā pragamyam/

64.01cd śarīracihnair adhunā bravīmi jaḍātmakārthaṃ śakunair nimittaiḥ//

64.02ab na vīkṣate yaḥ puruṣo dyumārge vaśiṣṭhabhāryāṃ ca tathā ca vatsām/

64.02cd ṣaṇmāsam agre pravadanti tasya saṃjīvitavyaṃ paṭhanapratāpāḥ//

64.03ab avīkṣyamāṇo dhruvam ambareśaṃ viṣṇoḥ padāni kṣititārakaṃ ca/

64.03cd saṃjīvate ‘bdadvibhir ākṛtaujā vinaṣṭacitto manujaḥ sudīnaḥ//

64.04ab yo vīkṣate mātṛgṛhaṃ † ca ulkāṃ yāyityamānaṃ ca śanaiścaraṃ ca/

64.04cd vyabhre ca vai pūrṇaśaśiṃ viraśmiṃ saṃjīvate vatsaram ardhahīnam//

64.05ab yaḥ khaṇḍabhāskaraṃ paśyed raśmihīnam athāpi vā/ [śloka]

64.05cd ulkayā hanyamānaṃ vā sa jīvate dinatrayam//

64.06ab śakrāyudhaṃ paśyati yo niśāyaṃ divā ca bhāni prabhayā yutāni/

64.06cd sa māsam ekaṃ manujo ‘tra loke saṃjīvate ‘sau vibhavair vihīnaḥ//

64.07ab dṛṣṭvā ca kākaṃ surataprasaktaṃ mārjārakaṃ vā dviradaṃ ca martyaḥ/

64.07cd māsadvayaṃ jīvati duḥkhayuktaḥ sarpaṃ ca siṃhaṃ sarabhaṃ śṛgālam//

64.08ab † paśyarṣabho barhi ca pīyate go svayaṃ ca vā go pibate svadugdham/

64.08cd māsatrayaṃ varṣayutaṃ pumāṃś ca saṃjīvati sma svajanābhibhūtaḥ//

64.09ab kabandham ālokayate ‘mbarasthaṃ yo rākṣasaṃ vātha piśācakaṃ vā/

64.09cd māsāṣṭakaṃ jīvati tatparaḥ saḥ prabhūtakośākulito manuṣyaḥ//

64.10ab rātrāv ulūko gṛhamūrdhni saṃstho yasya pravāraṃ kurute trivāram/

64.10cd saṃvatsareṇa pradadāti mṛtyuṃ narasya tasyādbhutarogapārśvāt//

64.11ab gṛdhro yadā vāyasapotako vā śiraḥ samārohati yasya puṃsaḥ/

64.11cd sa saptamāsād bahuduḥkhabhāgī jīvet tato vātha kapotakaś ca//

64.12ab khaṇḍaṃ padaṃ yasya narasya paṅke naraṃ pradattaṃ hy athavā ca dhūlyām/

64.12cd saṃvatsarārdhaṃ pravadanti tasya śaṃśanti śāstrārthavidāṃ variṣṭhāḥ//

64.13ab vyaṅgaṃ samālokayati kṣaṇaṃ yaś chāyāpumāṃsaṃ śanijaprasūtam/

64.13cd aṅgādhikaṃ vā sakalaṃ na paśyet sa māsam ekaṃ puruṣo ‘tra jīvet//

64.14ab ādarśake vā ghṛtatailamadhye na paśyati svaṃ vadanaṃ naro yaḥ/

64.14cd vyaṅgaṃ samālokayati sma jīvet ṣaṇmāsakaṃ vā bahuhīnarogaḥ//

64.15ab saṃjāyate yasya narasya gātre kugandhavaktraṃ vraṇavarjitaṃ ca/

64.15cd varṇasya nāśaṃ † sumaro na bāhyaṃ sa varṣam ekaṃ yadi jīvati sma//

64.16ab yo nāsikāgraṃ na naraḥ prapaśyej jihvāgrabhāgaṃ na ca pṛṣṭibhāgam/

64.16cd sa jīvate varṣam iti pradiṣṭaṃ mahāmunīndrair yavanapradhānaiḥ//

64.17ab snātasya yasyāśu karau ca pādau saṃśuṣyate † vatsahitau narasya/

64.17cd sa māsam ekaṃ śaradaṃ ca jīvet pipāsitasyā † havate ‘thavā hi//

64.18ab vāmāṅgabhāgaḥ sphurate narasya yasyākṣiyugmaṃ satataṃ trirātram/

64.18cd māsatrayaṃ jīvati tatpare saḥ † kṣatārtabandhuprabhum asya yānaḥ//

64.19ab pūrīṣamūtraṃ kurute prabhūtaṃ yaḥ svasthatāḍhyo ‘pi naraḥ sa jīvet/

64.19cd saṃvatsarārdhaṃ prabhutāśano vā bhaved akasmān maraṇaṃ narasya//

64.20ab mitrair virodhaṃ kurute pumān yo maitraṃ dviṣaḍbhiḥ patitaiś ca hīnaiḥ/

64.20cd sa jīvabhāgī bhavatīha varṣaṃ vidveṣakopaś ca suradvijānām//

64.1 [As explained in the previous chapters,] all the auspicious and inauspicious [effects] resulted from the planets should be understood with good understanding. Now, I shall speak for the sake of the dull-witted (jaḍātmakārtham),[1] with bodily signs and the bird omens.

[Astral/meteorological phenomena]

64.2 If a man does not see by the way of the sky (dyumārge) the wife of Vaśiṣṭha (i.e., Arundhatī, or the star Alcor),[2] the ones eminent in learning (paṭhanapratāpāḥ) predict that he will live up to six months.[3]

64.3 If one does not see the Pole Star (dhruvam), the Sky Lord (ambareśam) and the faint star (kṣititārakam, i.e., Arundhatī), that is, the steps of Viṣṇu (viṣṇoḥ padāni < viṣṇoḥ padāntam),[4] the very poor man whose strength is spent (ākṛtaujā) and whose mind is lost will live for two years (abdadvibhir [sic] < abdadvābhyām).

64.4 If one sees in a clear sky (vyabhre) the “house of the mother” (mātṛgṛham?),[5] falling meteor (ulkām), Saturn (?),[6] and a dull Full Moon, then [the person] will life for half a year.

64.5[7] If one sees an eclipsed Sun (khaṇḍabhāskaram), a lusterless [Sun] or [a Sun] struck by a fiery phenomenon in the sky (ulkayā), he will live for three days.[8]

64.6 If one sees a rainbow (śakrāyudham) at night and stars with light during the day, such man will live for a month in this world without strength.[9]

[Animals]

64.7 If a person sees a crow, a cat, or an elephant, a snake, a lion, a monkey or a jackal in heat (surataprasaktam), he will live for two months in misery.

64.8 If a bull, a peacock (barhis<barhi?) and a cow are seen drinking on their own (?), or if a cow drinks its own milk, then the man will live for one year and three months, injured by his own people.

64.9 If one sees [the phantasm of] a headless man (kabandham),[10] a demon or a piśāca in the sky, following that, the man would be distressed with his great wealth and live for eight months.

64.10 If an owl makes the choice to be on the roof of the house thrice in the night, one predicts the death of the person to whom the house belongs to be within a year, resulted from acute sickness of one’s sides (adbhutarogapārśvāt).

64.11 If a vulture, a birdling or a pigeon lands on the head of a person, the person would live for seven months experiencing great suffering.

[Human and bodily parts]

64.12 If foot of a man becomes broken in the mud or when it is placed in the dust, the best of those who know the meanings of the śāstras predict [the person to live] half a year.[11]

64.13 If one sees for a moment a limbless cripple, man[-shaped] born of Saturn, and does not see full or additional [limbs], he would live for a month in this world.

64.14 If a man does not see his own face in the reflection of ghee or sesame oil, [but] sees a limbless cripple, he would live for six months with a severe crippling disease.[12]

64.15 If a man’s mouth has no wounds but is foul-smelling, and if he lives for one year, there will be ruin of [his] caste, [but] he will have a good death, not ostracized [in his caste] (?).

64.16 If a man does not see the tip of [his] nose, part of the tip of [his] tongue or part of his rib (pṛṣṭibhāgam), the great sages, it is predicted by the best of the Yavanas that he will live for a year.[13]

64.17 If the hands and feet of a man after being washed… (vatsahitau?)[14] are completely dry, or if he calls while he was thirsty (pipāsitasyāhavate ?), he would live for one year and one month.[15]

64.18 If the left part of a man’s limbs and both eyes twitch constantly for three nights, following that he would live for three months, while he was traveling to the lord of [his] kin afflicted by wounds (kṣatārtabandhuprabhum asya yānaḥ?).

64.19 If a man who eats a lot defecates and urinates in a great quantity although he is healthy, he would either live for half a year or dies suddenly.[16]

64.20 If a man creates hostility with friends and makes friendship with wicked and vile enemies, he will live in this world for a year, with hate and anger of gods and the twice-born.

[1] Svapnātmakārtham (“meaning of the nature of dreams”)? An emendation seems necessary since the topic of dream occupies a significant portion of the chapter.

[2] On Arundhatī as Vaṣịṭha’s wife, see Raghuvaṃśa 1.56, BS 13.6.

[3] Cf. Carakasaṃhitā 5.11.5, for death in one year under same condition: saptarṣīṇāṃ samīpasthāṃ yo na paśyaty arundhatīm/ saṃvatsarānte jantuḥ sa saṃpaśyati mahattamaḥ// Also, Aṣṭāṅgahṛdaya (śārīra) 5.33, Suśrutasaṃhitā (sūtra) 30.20. Immediate death is prescribed in two verses attributed to Gopura in Ṭoḍarānanda (Meulenbeld 1999: IIA. 293; see notes on next verse).

[4] Cf. na paśyati sanakṣatrāṃ yas tu devīm arundhatīm/ dhruvam ākāśagaṅgāṃ ca taṃ vadanti gatāyuṣam (Suśrutasaṃhitā I.30.20). Note the combination of Arundhatī, Pole Star, and Milky Way. Also: arundhatī dhruvaṃ gaṅgāṃ viṣṇos triṇi padāni ca/ āyurhīnāḥ na paśyanti caturthaṃ mātṛmaṇḍalam // (Ṭoḍarānanda II.5.62). “Persons, who have no pan of life left cannot see the three steps of Viṣṇu, viz., Arundhatī, Dhruva and the Gaṅgā of the sky, as well as the Mātṛmaṇḍala.” Further explanation is given following the same verses: arundhatī bhavej jihvā dhruvo nāsāgram eva ca/ bhruvor madhye viṣṇupadaṃ nābhi syān mātṛmaṇḍala (Ṭoḍarānanda II.5.63-64). “Arundhatī is the tongue, Dhruva is the tip of nose, Viṣṇupada is the mid-point between the two eyebrows, Mātṛmaṇḍala is the umbilicus of Viṣṇu. The Gaṅgā in the sky is te path of the gods.” (Dash and Kashyap trans., same for below). I have emended padāntam to padāni to assume the steps of Viṣṇu to refer to the three celestial objects.

[5] Related possibly to Mātṛmaṇḍala, glossed by some as stars (tārakā) according to Ṭoḍara (Ṭoḍarānanda II.5.65).

[6] Śanaiścaraṃ here is not so satisfactorily. The original appears to be some incidental atmospheric phenomena such as aurora or lightening. ulkāśanidhūmādyair hatā vivarṇā viraśmayo hrasvāḥ// hanyuḥ svaṃ svaṃ vargaṃ vipulāḥ snigdhāś ca tadvṛddhyai// (BS 13.7). “If the Sages should be crossed by meteoric falls, thunderbolts, or comets, or if they should appear dim or without rays or of very small disc, thy will cause misery and suffering to the persons and objects they severally represent; but if they should appear big or bright there will be happiness and prosperity” (Iyer trans.).

[7] Anuṣṭubh. The change of meter is unusual.

[8] Cf. BS 4.28 for death of a king when a Moon is struck by a meteor.

[9] tārā diva dikṣurajo nipātaṃ yo vidyutaṃ paśyati ca nirabhre/ indrāyudhaṃ ca svayam eva rātrau māsādvayāt tasya vadanti nāśam (Ṭoḍarānanda II.5.69). “A person who sees stars during daytime, dust in different directions when they are actually clear, lightening when there is no cloud and rainbow during night, he succumbs to death within two months.”

[10] Utpala glossed kabandha as chinnaśirāḥ puruṣaḥ (BS 3.8).

[11] khaṅjaṃ padaṃ yasya bhavet kadā cit paṅkākule vā pathi pāṃsule vā/ sa pañcame māsi vihāya sarvaṃ prayāti yāmyaṃ sadanaṃ manuṣyaḥ (Ṭoḍarānanda II.5.82). “If a person becomes lame by accidentally entering into a place having mud or on a road having ash, he dies within five months.”

[12] ghṛte taile jale cāpi darpaṇe yas tu paśyati/ śirorahitam ātmānaṃ daśarātraṃ sa jīvati (Ṭoḍarānanda II.5.77).

[13] Nāsāgraṃ rasanāgraṃ ca cakṣuṣaivoṣṭhasaṃpuṭam/ yo na paśyet purādṛṣṭaṃ sa caturthe ‘hni gacchati // (Ṭoḍarānanda II.5.70, attributed to Gopura?). “If a person cannot see the tip of his nose, tip of his tongue and his lips through his eyes, even though he had seen them earlier, then he succumbs to death on the fourth day.”

[14] Vasāsahitau? ([even] “with ointment”)

[15] snātamātrasya yasyaiete trayaḥ śuṣyanti tatkṣaṇāt/ hṛdayaṃ hastapādau ca ṣaḍrātraṃ tasya jīvitam (Ṭoḍarānanda II.5.72, attributed to Gopura?). “If immediately after taking bath, three places, viz., heart, palms, and soles of the feet get dried immediately, then he lives only for six nights.”

[16] Reading unsatisfactory. This verse is possibly related to: durbalo bahubhuṅkto vā svalpamūtrapurīṣakaḥ/ svalpaṃ vā yas tu saṃbhuṅkte bahumūtrapurīṣakaḥ // nāsikāṃ spṛśate vāpi sa yāti yamammandiram / iti saṃkṣepataḥ proktaṃ granthavistārabhītitaḥ // (Ṭoḍarānanda II.5.119-120, attributed to Agniveśa).