In India, the Hindus celebrate the New Year from the month of Caitra which begins from the New Moon, and in which the Sun enters “Aries” (Sanskrit: meṣa). Whereas, in Southeast Asia and certain parts of India such as Bengal, the New Year starts directly from “the moment the Sun enters Aries” (Sanskrit: meṣasaṃkrānti = Thai: songkran). Since the Gregorian calendar is solar, the latter Indian (solar) New Year is more or less fixed at around Apr 14/15. The former (luni-solar) Indian New Year is always close to the latter, but moves around depending when the New Moon is.

But what is the true significance behind either of these New Years?

Just like all the calendars, Gregorian, Chinese, etc., they preserve a distant memory of the past. The latter Indian New Year was originally associated with spring, when the vernal equinox was located in Aries at around 400 CE. (Due to precession, the equinoctial point has now moved to Pisces). This coordinate system was originally developed by the Greco-Babylonian astronomers a few centuries before the common era and was adopted by the Indian some centuries after the common era. Prior to that, the Indians used only a luni-solar calendar like the Chinese.

The concept behind the former luni-solar Indian New Year beginning with Caitra is therefore much older. In the Vedas, Caitra is associated with spring (vasanta) as well, but was associated with the vernal equinox at a much earlier date at least a thousand years earlier, located in the nakṣatra Kṛttikā (close to Taurus).

Although both the contemporary Indian New Years are completely arbitrary, tied to Aries which carries greater meaning in astrology than in astronomy, we can nonetheless see beautifully how precession brought us from Taurus (former luni-solar India New Year), to Aries (latter solar Indian New Year), and to finally Pisces (where vernal equinox is currently located).

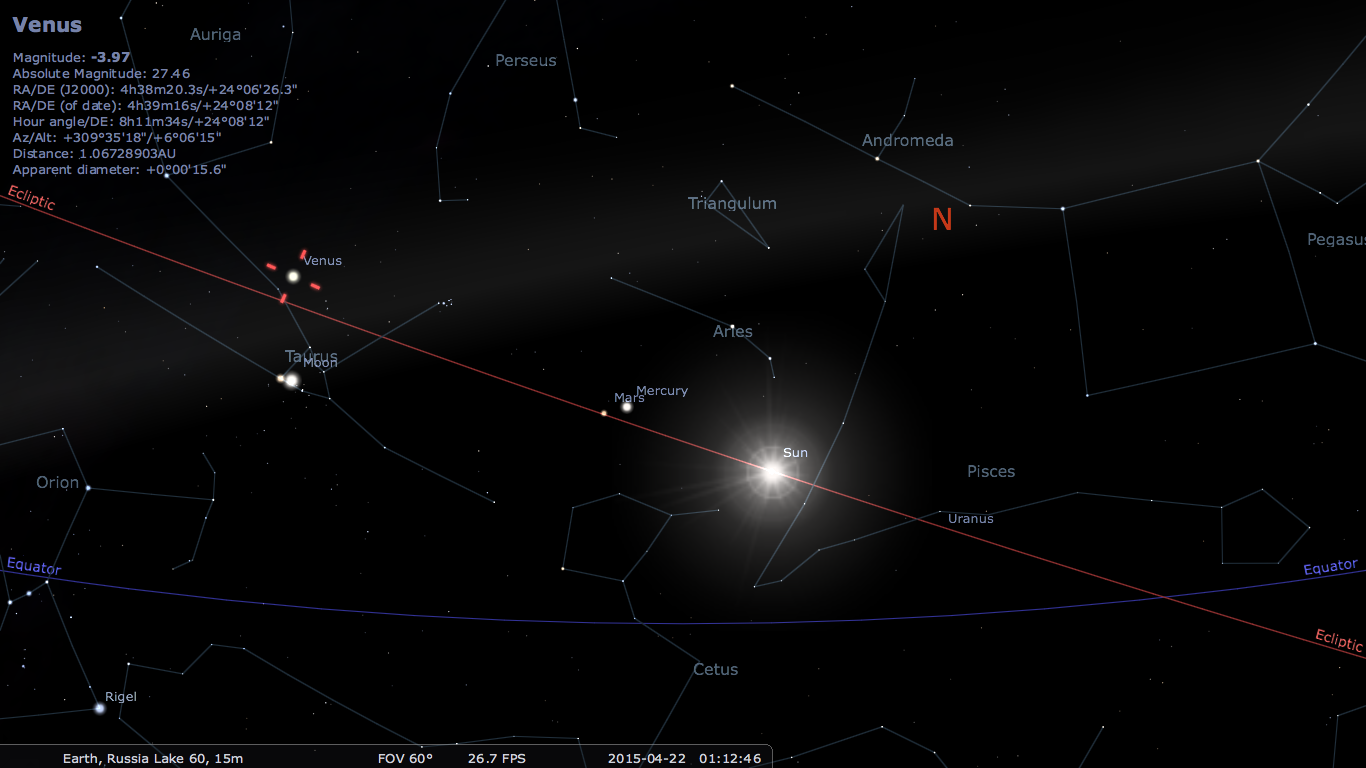

While on the topic of astral science, I should point out that today we have the Sun, Mercury, Mars in Aries and the Moon in Taurus.

A belated happy new year to all my friends who celebrate the Indian New Year(s)!